- Author Mondher Khanfir

- date de publication 07 Janvier 2024

According to World Bank data, Africa accounts for less than 3% of global production and international trade, yet over 16% of the world’s population lives on the continent. Faced with multiple and multidimensional crisis (health, security, political, climate change, etc.), investments in infrastructure struggle to take off, and intra-African trade remains limited, accounting for only 15% of the continent’s total trade with the rest of the world.

For instance, Sub-Saharan Africa could gain a minimum of 2% per year in economic growth and over 40% in productivity with adequate infrastructure that promotes regional integration. Currently, only 38% of the African population has access to electricity, less than 10% are connected to the Internet, and only 25% of the African road network is paved. The financial deficit to bridge this gap in infrastructure services is estimated between 59 and 100 billion US dollars annually, with a commitment of 81 billion US dollars in 2020, down from the historical record of 100 billion US dollars in 2018.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), advocated by the African Union, aims to give new dynamics to intra-African trade and investment through several strategic initiatives, such as regulatory and institutional alignment, the removal of non-tariff barriers, and the acceleration of infrastructure projects of continental corridors.

However, the reconfiguration of supply chains and global connectivity, critical elements in the master plan of continental infrastructure, are not always considered in country-level investment strategies.

From Infrastructure to Infrastructure Ecosystem

The concept of infrastructure has evolved over time from a set of works of art or technology to a system of assets linking or feeding value chains. It is now defined as a continuum of « physical artifacts, inputs, activities, and outcomes that aim to create, provide, and capture economic, social, and environmental values throughout a planned service lifecycle. »

Traditionally, infrastructure economic models revolve around two axes: the mode of provision (on-demand or rental/license/subscription) and the transaction channel (GtoBtoB, GtoBtoC, GtoC).

The low profitability characterizing these traditional economic models means they don’t attract many private investors unless land privileges or significant tax relief are granted.

A way to enrich economic models is to adopt a systemic view of the infrastructure, associating all the activities from the pre-construction phase to the operational phase as part of a global development ecosystem. This infrastructure ecosystem, as considered here, includes all objects and subjects that design, finance, produce, and manage the expected services, as well as the environment that enables them to deploy and extend their scope of application.

Adopting a systemic view acknowledges that infrastructure is not just about physical construction but involves a social capital and a complex network of stakeholders. This perspective helps in understanding and managing the interdependencies within the infrastructure ecosystem, leading to more efficient and effective project execution.

Incorporating all phases of development including activities from the pre-construction phase (like planning and design) to the operational phase ensures a comprehensive approach. This can lead to better foresight in the planning stage, cost-effective execution during construction, and enhanced sustainability and viability in the operational phase.

Nevertheless, this approach inevitably includes regulatory and institutional frameworks that become structuring elements of the service performance, requiring governance capacity and risk management. The reference to an environment that enables deployment and extension of scope highlights the need for adaptability and scalability in infrastructure projects. This is particularly important in a rapidly changing world where technological advancements and shifting socio-economic conditions can quickly render rigid infrastructure obsolete.

This holistic and dynamic approach to infrastructure development aligns with modern principles of sustainable development and can lead to more resilient, inclusive, and effective infrastructure systems. It’s particularly relevant in regions like Africa, where there is a need to leapfrog traditional development pathways and embrace innovative and integrated solutions for rapid and sustainable growth.

Thus, technological integration into this infrastructural ecosystem model will lead to innovative economic models, ensuring sustainability, impact and the rapid achievement of a higher profitability threshold, making it possible to justify sources of financing other than public or institutional. It is up to OEMs and EPCs to innovate and control deadlines, overall costs, impact and quality throughout the life cycle of their works in a logic of overall cross-sector and cross-border performance.

The integrated infrastructure ecosystem paradigm applies particularly well to connectivity infrastructures (designated Corridors), which must ensure sustainable competitive advantages based on elements other than the lowest price criterion.

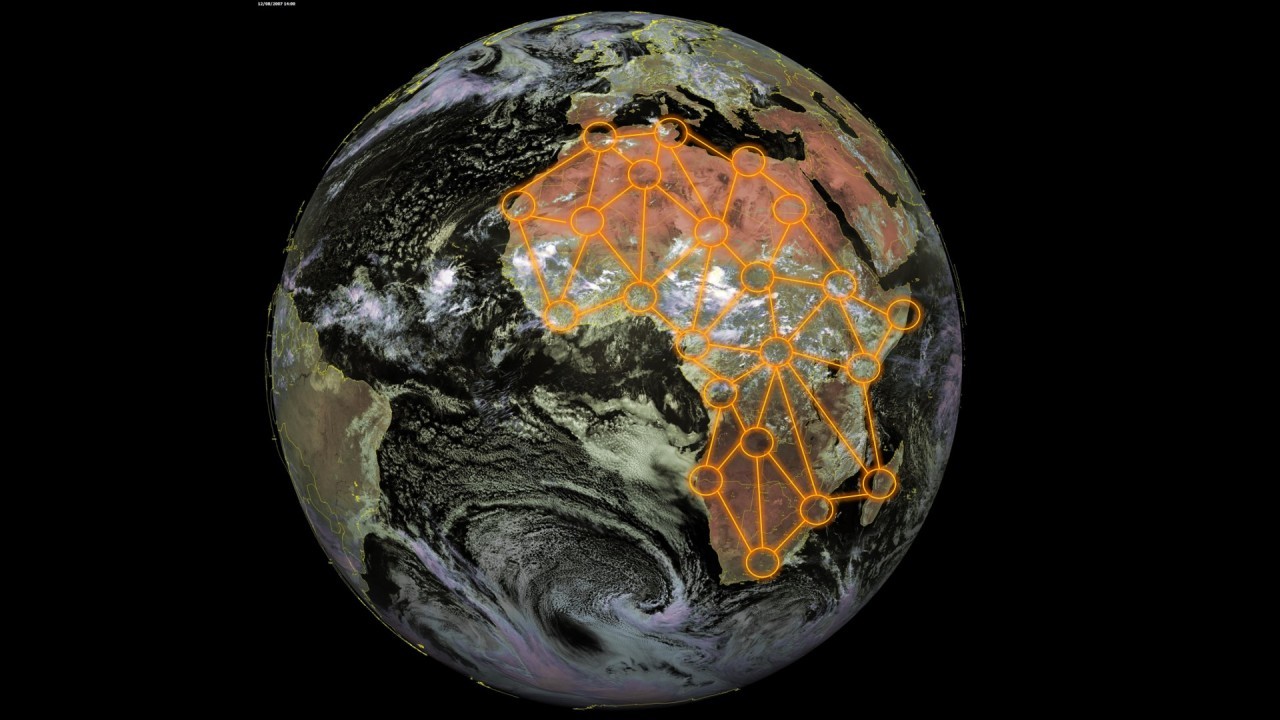

This led to the development of a holistic infrastructure planning framework by AUDA-NEPAD in order to identify a batch of priority projects (in fact the PIDA-PAP2 batch) promoting regional integration in Africa -cf. figure 3-

Towards Integrated Infrastructure in a Global Economic Corridor 2.0 Model in Africa

By adopting an ecosystemic approach to infrastructure development, African governments have the potential to innovate and maximize the impact of their investments in a new generation of Corridors that enhance the value added by new technologies (digital, climate adaptation, and other innovative technologies). This can be achieved by leveraging the collective capacity of a wide range of stakeholders at all stages of infrastructure design and implementation.

The development requirements of Corridors 2.0 raise acute issues of specifications, standardization, coordination among various stakeholders and countries, and governance of the entire infrastructure ecosystem. This is the rationale behind the Accelerating and Scaling-up Quality Infrastructure Investment in Africa (ASQIIA) initiative, driven by the OECD, AUDA-NEPAD, and ACET after an in-depth study titled « Quality Infrastructure in Africa in the 21st Century. »

For Corridors 2.0 to be operational, they need junction points and potential exchange flows, including data. They can thus deploy global value chains by interconnecting logistical-industrial hubs or digitized special economic zones. These zones are evolving towards positioning as integrated regional marketplaces or clusters within national economies.

Africa’s productive transformation will be achieved through the liberalization of regional trade and a geopolitics of infrastructure integrated into Corridors 2.0. Sharing best practices, enriching the economic models of infrastructure, and pooling their financing through dedicated funds can accelerate this process. According to the Economic Commission for Africa, the continent could generate about 82 billion dollars per year in Carbon Credit if the carbon price remains around 100 US dollars per ton. An opportunity for financing Corridors 2.0. The challenge remains to create the right governance bodies and investment vehicles for Climate Finance, new pieces that will enrich the African infrastructure ecosystem.